Our mission

Our mission

The Farm to Crafts project seeks to enhance the self-sufficiency of the Curaçao economy by creating new ecosystems that connect the social, ecological, and cultural sectors.

Our Vision

Our Vision

By farming our own resources

By farming our own resources

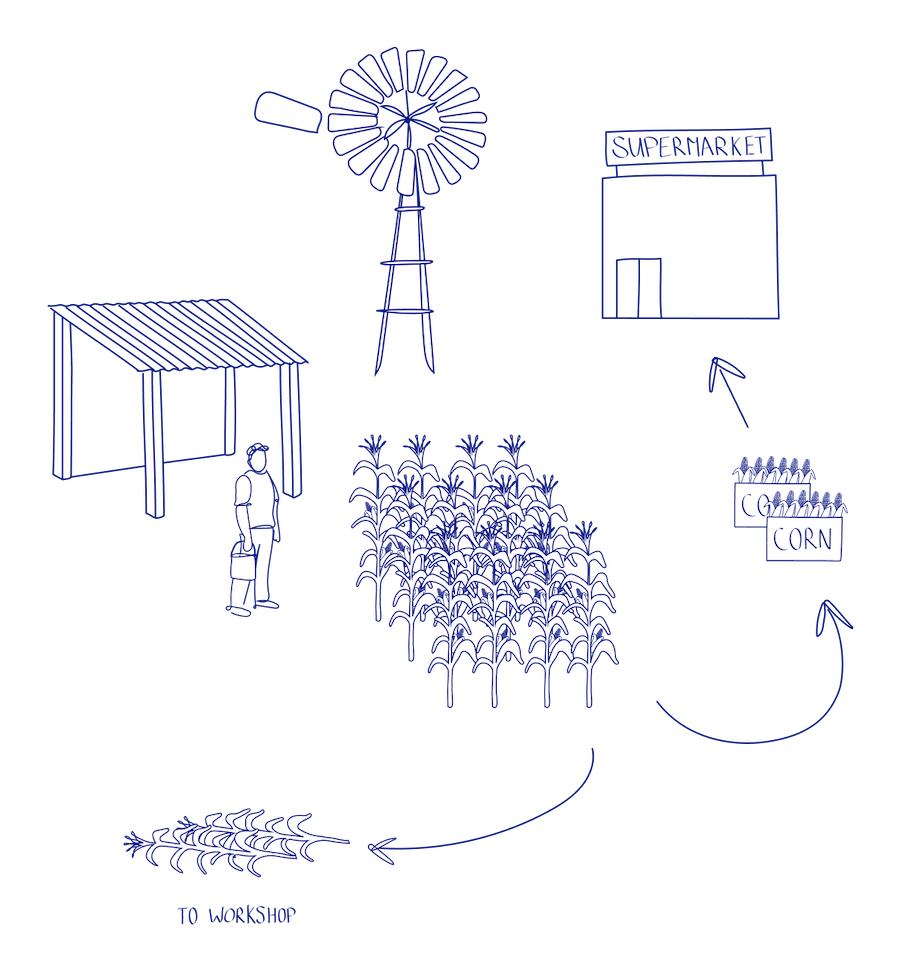

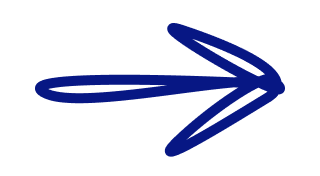

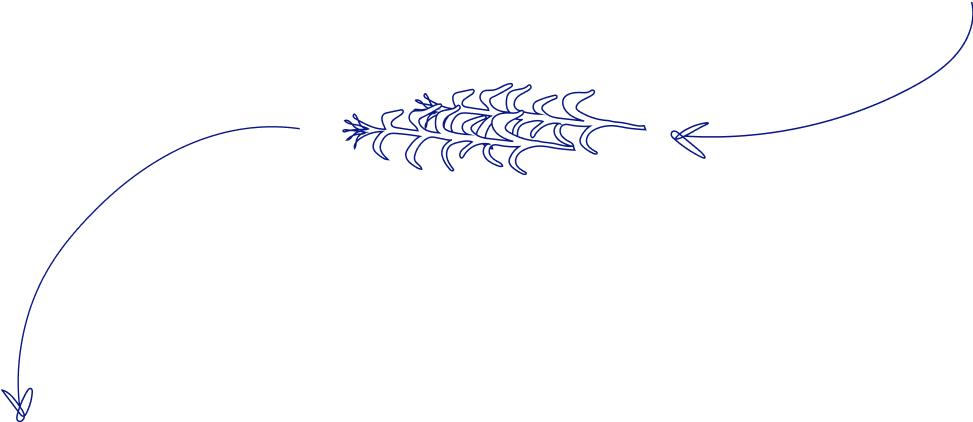

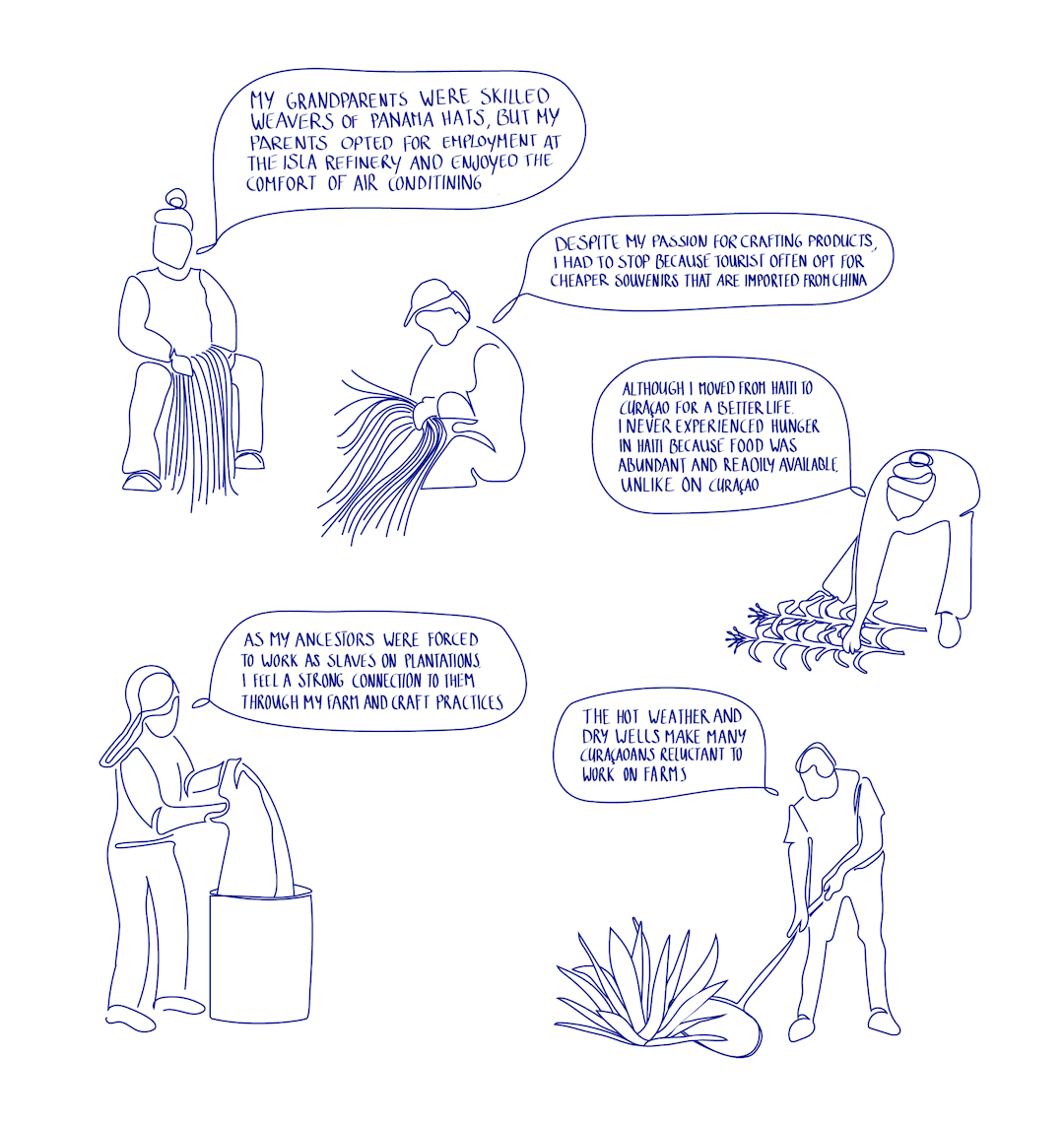

Curaçao depends on foreign sources for 95% of its food supply. One of the many challenges faced by farmers on the island are the “unfair prices” that supermarkets are willing to pay for their products. Farmers are under pressure due to the island’s climatic conditions, but organizational barriers make them even more vulnerable. By researching alternative “non-food” options for farmers we aim to help increase the sector’s resilience in the future. Farm to Crafts promotes the circular economy and regenerative agriculture, utilizing, among other things, residual products from already grown crops and introducing new crops to make optimal use of space. The material flow brings more cohesion between sectors that currently do not cooperate.

we can promote the growth and sustainability of the crafts domain

we can promote the growth and sustainability of the crafts domain

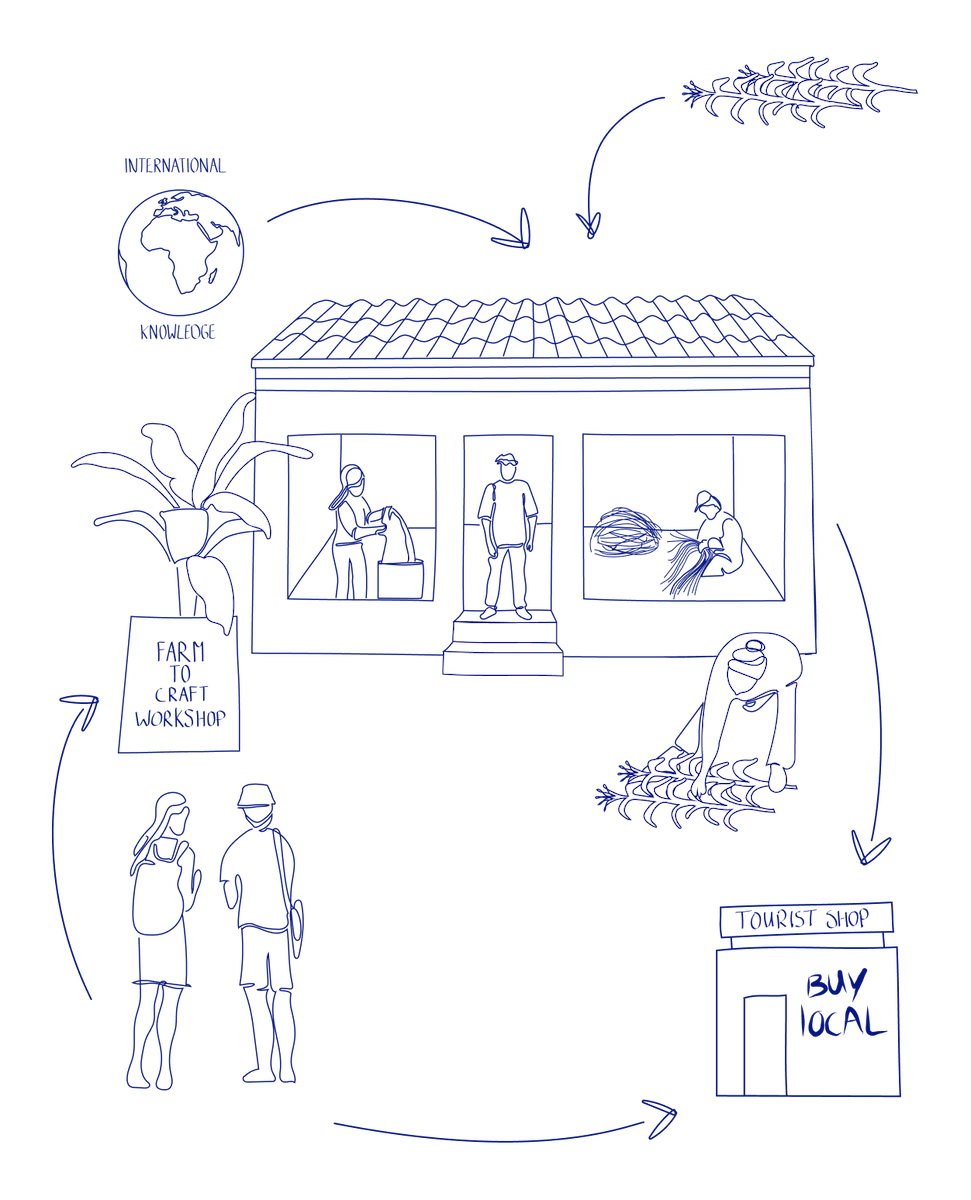

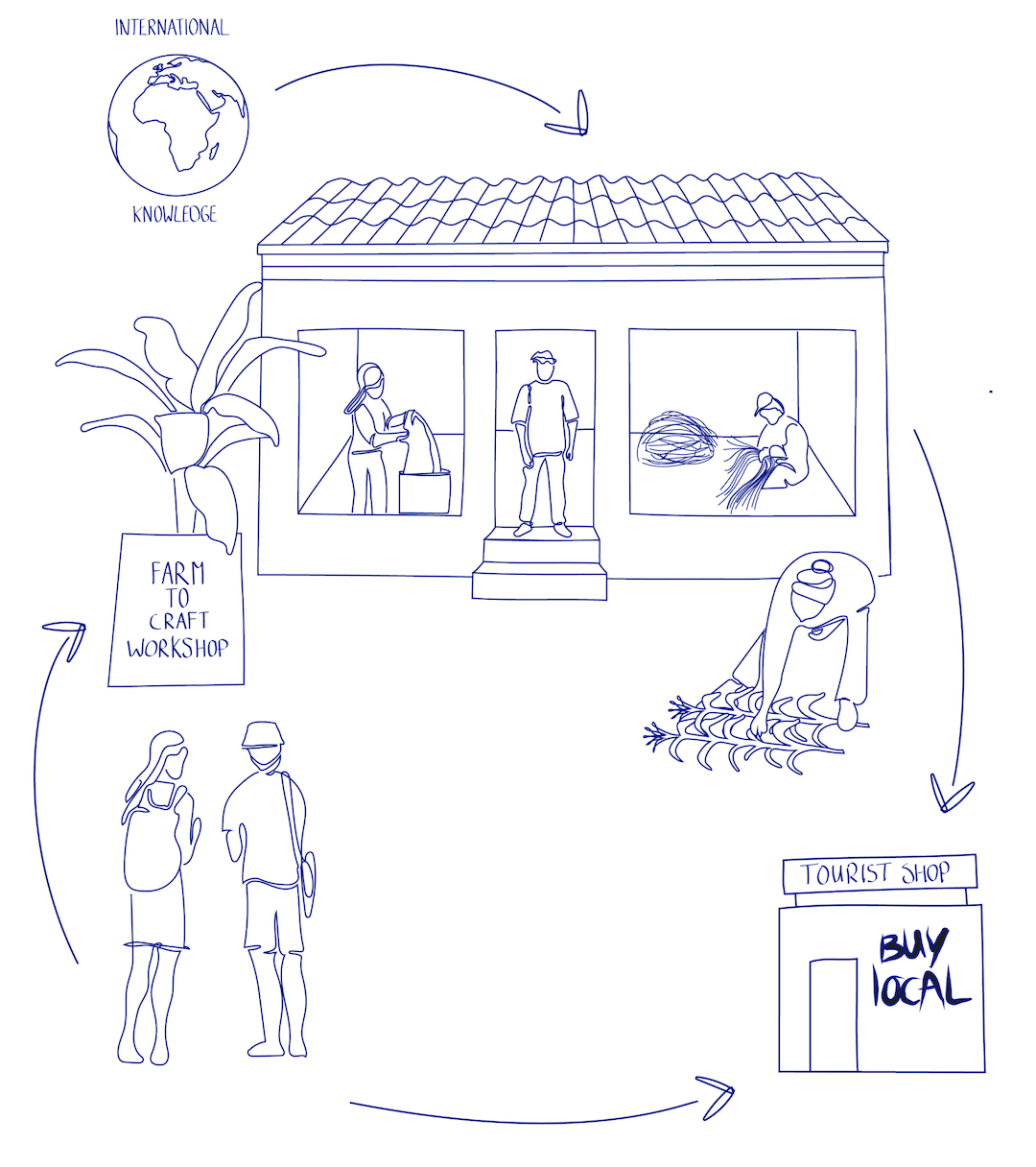

The Farm to Crafts team envisions a thriving creative manufacturing industry in Curaçao, centered on locally grown, renewable resources. This would not only provide much-needed jobs for unemployed individuals, but would also meet the fast-growing touristic demand for local artisanal products. We see potential for eco-tourism as well. The trends in tourism suggest a desire for a more active and meaningful holiday experience. Future tourists are interested in experiencing nature and gaining new insights by participating in local culture, learning about local customs and skills. We believe that the Farm to Crafts project can provide such an experience in a uniquely Curaçaoan ecosystem consisting of farmers, artisans, and local entrepreneurs.

while also honoring our past.

while also honoring our past.

In the past, Curaçao’s natural resources were exploited during the colonial era, leading to the loss of ancient indigenous knowledge and artisanal skills. Traditional Curaçaoan crafts, such as weaving Panama hats and creating filigree work, are scarcely visible today. The legacy of our slavery past has shaped the current perception of agriculture and craftsmanship, with farming and crafting still widely viewed as work imposed upon enslaved people. Through the Farm to Crafts project, we strive to foster conversation, understanding, and connection through agricultural and manufacturing processes.

Articles, events and insights

Articles, events and insights

We are organizing several events where regional and international artisans, designers, and experts will share their vision and experience with the Farm to Crafts community. These workshops offer hands-on learning opportunities for sustainable farming and crafting techniques, providing valuable insights and takeaways for participants. This section informs you about what to expect from our events, and emphasize the insights and learning that come from our process.

Farm to Crafts finds its footing with banana fibers

Nienke Hoogvliet's presentation at The Cathedral of Thorns attracts the largest crowd till date. Despite it being a weekday, in the midst of the busy carnival season, it's a full house. The Dutch…

Mix and Match: The Beauty of Curaçao Fibers

A coconut by the side of the road. Banana leaves on the ground. Designer Sanne Muiser views nature through the lens of fibers, and Curaçao is a treasure chest where fibers exist in large numbers. As…

How we work

How we work

Farm to Crafts is a social design project initiated by the Designing perspectives foundation. Social design is a discipline that uses design principles and methodologies to address complex social problems. It involves the application of design thinking to create solutions that are effective, sustainable, and socially responsible. We are driven by the following principles:

Learning by Doing

Our approach emphasizes hands-on, experiential learning. This means that learning takes place through actively engaging in the creative process itself, rather than simply studying or observing it. This way we believe to develop a deeper understanding of the creative process and the materials, tools, and techniques involved.

The power of experience

Creating meaningful and enriching experiences for participants and visitors is a key goal of the Farm to Crafts project. By providing opportunities for engagement and interaction, Farm to Crafts aims to foster a dynamic environment for creative research and production.

Co-creation

We facilitate interactions based on participation and reciprocity. We want to offer a broader perspective and convey that you can create opportunities by taking the lead. A bottom-up development process provides the greatest chance for an inclusive design, where the wishes of those involved are co-determining for the process.

Diversity

Those involved all have different backgrounds and expertise. We emphasize the importance of multidisciplinary collaboration and the inherent connections between cultural heritage, education, agriculture, design, craftsmanship, and the economy; especially on a small island like Curaçao."

Historic perspective

Historic perspective

1 6 5 1 ——— 1 8 1 6 —— 1 8 8 0 —— 1 6 8 0 ——— 1 8 1 6——— 1 8 1 7 ——— 1 8 4 4 ——— 1 8 6 0 —— 1 8 3 7 ———— 1 8 9 8 —— 1 9 0 7 ———— 1 9 2 0 ——— 1 8 4 0——

1 6 5 1 —————— 1 8 1 6 ———— 1 8 8 0 ———— 1 6 8 0 —— 1 7 9 1 —— 1 8 1 6 ———— 1 8 1 7 ————— 1 8 4 4 ————— 1 8 6 0 ———— 1 8 3 7 ————— 1 8 9 8 ————1 9 0 7 ————— 1 9 2 0 ———— 1 8 4 0 ——

Indigo

The indigo plant (Indigofera tinctoria) was used as a source of blue dye for textiles. The plants were introduced by the Dutch, and its culture probably started as early as 1651 when the first Jewish settlers arrived on the island. Using local stones and imported yellow ijsselsteentjes (bricks), they built indigo basins in which the indigo leaves were soaked to reach fermentation . Subsequently the indigo was moved to two lower lying basins. The result was a colored liquid that was dried and packed. The unpleasant smell of the process forced the plantation owners to place the indigo basins as far from the main house as possible.

Especially in the 18th century the indigo culture was widespread. In 1803 the inventory of St. Nicolaas plantation mentioned tools of the indigo culture, but it is unclear whether indigo was still cultivated there at the time.

It has been established, though, that after 1816 the indigo culture on the island was of little account. Because the English had actively stimulated the culture in British India, market prices plummeted. Growing indigo proved no longer profitable for the small Curaçao producers, and the indigo culture dwindled.

The indigo plant still grows in the wild on the island, and remnants of the culture can be found on several (former) plantations. So far, the Archeological Study Group, popularly referred to as the “Detectives” (Speurneuzen), have found 23 sets of indigo basins on 16 former plantations.

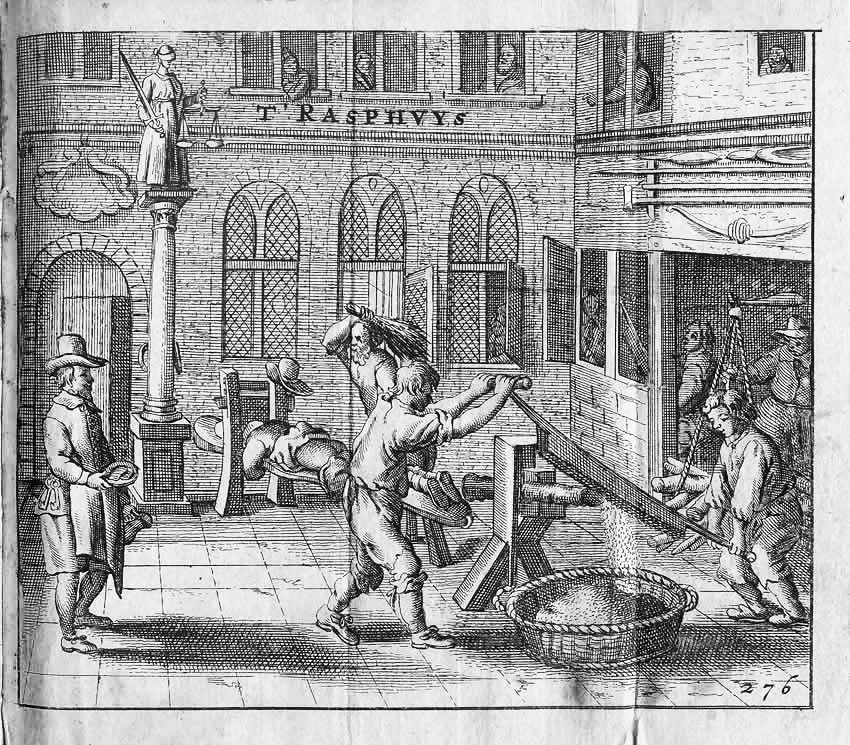

Dyewood/Brasilwood

When the Spaniards discovered Curaçao, dyewood grew in the wild all over the island. It was used to make a red dye for textiles. To that end the wood was shipped to Europe. In Amsterdam, inmates of a detention center used to rasp the wood to a powder. This powder was turned into the dye named Brasil.

For quite some time the Amsterdam detention center had the monopoly of rasping dyewood. Because of this activity, it was even nicknamed the Rasp House.

Curaçao had less brasilwood than the neighboring island of Bonaire. Besides, the trees grew far from the coast, so they had to be transported over long distances. Nevertheless, in the first one and a half years of Dutch occupation no less than twenty ships with dyewood left for the Netherlands.

Since neither the Spanish nor the Dutch colonizers bothered to replant the chopped trees, the quantity of brasilwood declined rapidly. By the end of the 17th century trade in dyewood from Curaçao was as good as over.

In the 19th century, however, there was a revival. Since in the previous century hardly any dyewood had been chopped, the amount of timber had grown back. So dyewood was once again chopped on a few plantations, especially in Bándabou. In the 1880s the plantation of Savonet was an important supplier of dyewood. By the start of the 20th century demand for dyewood decreased.

Cotton

Cotton used to be grown on Curaçao, but only in small quantities. In the 1680s a hundred spinning wheels were shipped from the Netherlands to the island, because Curaçao had top-quality cotton. It was the intention to develop the cotton culture, but a few years later caterpillars destroyed the entire crop. Subsequently, the culture was abandoned.

In 1791, a report once again stated the good quality of Curaçao cotton. According to the report its culture wasn’t worth mentioning. Still, in 1816 Jan Thiel plantation’s inventory mentioned ‘15 bags of cotton beans’. In the late 1820s the agricultural expert Teenstra observed that two types of cotton were planted on the island, mainly for private use. It was also seen growing in the wild.

That changed when Governor Van Raders (1836-1845) intended to promote cotton growing. He imported drought tolerant seeds from Barbados which were sown on Plantersrust. A year later the first bales of cotton could be shipped. Private plantations such as Siberie and Savonet followed.

But nature in the form of caterpillars put a spoke in the wheels. Complete cotton fields were eaten, and the cotton culture on Plantersrust was discontinued after only four years.

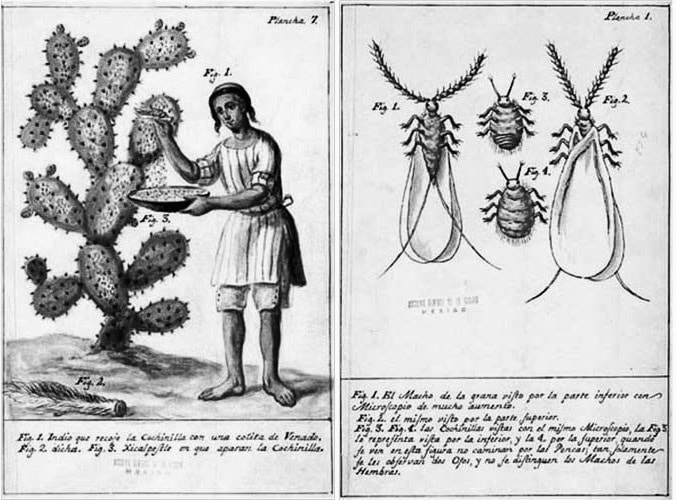

Cochineal

Cochineal is a dye produced by insects living on the nopal or cochineal cactus. When large enough, the insects are killed. To obtain the carmine dye, they are then dried and crushed. It takes two to three years before the plants produce enough sap for the cochineals to be placed on the cacti.

By 1817 governor Kikkert saw the economic possibilities of the cochineal culture, since the cacti grew on the island. But how to obtain the insects? It took until 1837 before the first cochineals arrived. Unfortunately, it soon appeared that the local plants weren’t suitable for the cochineal culture, so cochineal plants had to be imported as well.

Plantation owners showed little interest in this culture because they shied at the investments, which wouldn’t yield a return before the third year. Then Cornelis Sprock arrived on the island with the intention of starting a cochineal farm. To that end he bought the Cas Cora plantation in 1844. At that time, the government also planted two plantations with cochineal, and they did well. Gradually, more (private) plantations followed: Savonet, Siberie, St. Sebastian and Brievengat, also owned by Sprock.

In 1848, there were 247 acres of cochineal plants all over the island, but the bumper crops of 1847 and 1848 did not continue. It subsequently appeared that the abundant rains of 1847 and 1848 were responsible for the successful culture in those years.

In addition to the much drier following years, the price of cochineal reached an all-time low in 1849. Quite soon the government then withdrew from the cochineal culture, with the (temporary) exception of one plantation. Private plantation owners also abandoned the production of cochineal. From the 1860s onward, there were no more cochineal plantations on the island.

Cas Cora, where once the cochineal industry started, is now an ecological farm and restaurant. It is also the spot where ‘Farm to Crafts’ explores the revival of the cultivation of raw materials that can be used for local crafts.

Silk and silkworms

For more than 5,000 years silkworms have been bred in China for the production of raw silk. The larvae of silkworms feed on the mulberry tree leaves. When they reach their pupal phase, they enclose themselves in a pod made of a thread of raw silk. Its length can vary from 1,000 to 3,000 feet.

In Curaçao, silkworm-breeding to produce silk has never been successful. In 1837 mulberry trees were imported from Guadeloupe and Martinique, in 1838 another type of mulberry arrived from Utrecht, the Netherlands.

In that same year,1838, first lieutenant Frucht sailed to Guadeloupe by government order. He was asked to find out details about the mulberry and silkworm culture. On Guadeloupe, the Japanese mulberry was cultivated for its leaves because the silkworms preferred this type of mulberry. The fields weren’t irrigated, although it would sometimes not rain for four months. Silkworms were cultivated and fed with mulberry leaves in a shed.

Frucht took some silkworm eggs and pods with him to Curaçao, but it is unclear what was done with them. Although the imported mulberry trees did well on the island, in 1843 it was reported that the silkworm culture was a complete failure.

Nevertheless, in 1898 Samuel Cohen Henriquez of the Van Engelen plantation imported silkworms from Italy. Unfortunately, they were all dead upon arrival.

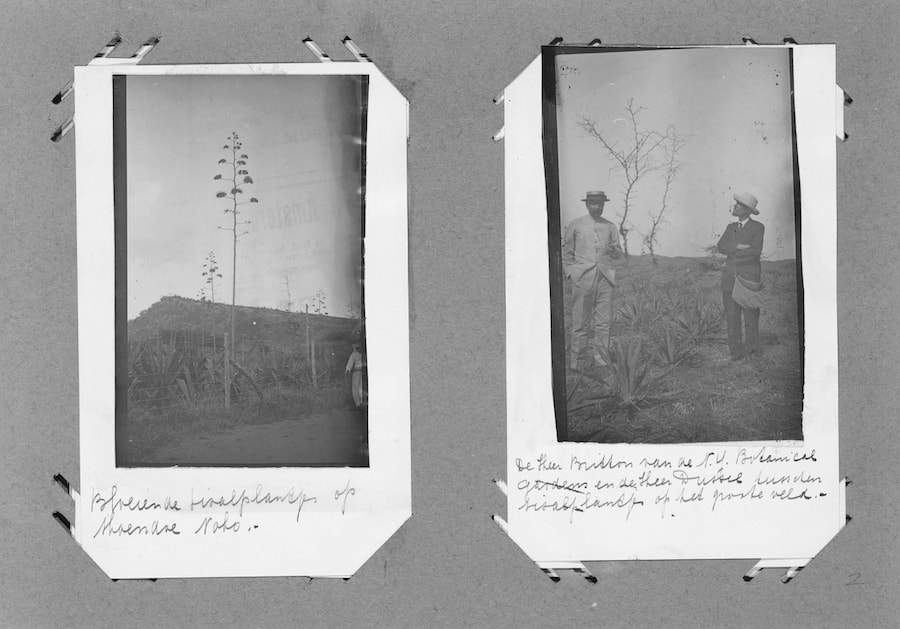

Agave/sisal

The first experiments with the agave culture date back to the 1840s. Unfortunately very few agave fibres were harvested. Then, at the turn of the last century, Samuel Cohen Henriquez, owner of the Van Engelen plantation, had a go at growing agave. He started a trial field of sisal on a plot between the plantations of Groot St. Joris and Koraal Tabak. In addition to his lack of any agricultural experience, the following years were extremely dry, so the young agave plants did not get enough water to fully develop. However, the island was desperate for new crops, so part of the Van Engelen plantation was rented to plant more agave plants.

Meanwhile, an Agricultural Society had been founded which planted 37 acres of agave on Plantersrust. Several more plantations experimented with sisal and the government bought a defibring machine. It was still unclear, though, which variety would yield the best crop on the island.

In the meantime, Cohen Henriquez started a ropery on his plantation in 1907. It was called Michiel de Ruyter and sold ropes in several thicknesses. Among other things, alpargatas were made from the ropes. The ropery was short-lived, because people preferred the better quality ropes from the States.

Two years later, the First Sisal Culture Company was founded. In 1910 it planted more than 100.000 agave plants, mostly from Surinam and Trinidad, on the Mount Pleasant plantation. It also bought a shredder for the sisal fibres. By 1918 the Sisal Society was led by Gijsbert d 'Aumale, Baron van Hardenbroek, who lived in the Mount Pleasant plantation house.

Despite the enthusiasm, the Sisal Company went bankrupt in 1920. This was partly due to dry spells, disadvantageous to the agave plants. All in all, the sisal culture proved economically unsuccessful on the island.

Straw or panama hats

Making straw hats is a centuries-old tradition on the island. From 1840 onward hat plaiting became an important home industry. Hats were exported to Santo Domingo, St. Thomas and even New York. Soon after, though, export went downhill because of the American Civil War and because fashions changed.

The beginning of the 20th century showed a revival lasting for more than two decades. A bumper year was 1912 when almost 1.7 million hats were exported. Also, they were popular with tourists as souvenirs.

To improve the quality of the hats, the Curaçao Company for the Promotion of Farming founded special plaiting schools where young women were taught to make top quality hats. The catholic church trained hat plaiters as well, for instance at schools for the poor.

Nowadays, only a handful of Curaçaoans still master the hat plaiting craft. Since straw hats, sombré di kabana, are worn as protection from the blazing sun and at the harvest festival Seú, they are now mostly imported from Ecuador, Haïti, the Dominican Republic and Venezuela,

Straw hats are made from the dried leaves of the Carludovica palmata, the panama palm. According to frater Arnoldo’s book about local plants, this palm tree does not grow on the island. The leaves used to be imported from Venezuela, Ecuador and Colombia. According to a hat plaiter from Bándabou, the leaves of the local panama palms tend to break when they’re too old. For delicate hats palm leaves from Cuba and Haiti were used. The leaves were cut lengthwise into long strips, a time-consuming job. After that, the plaiting could begin. The finer hats were then bleached and dried in the sun.

It was mostly women who applied themselves to hat making, but men would work in the hat industry as well.

-Research and stories by Jeannette van Ditzhuijzen

Meet our core team

Meet our core team

Cleo de Brabander

Initiator and creative director

Cindy Eman

Regenerative farming specialist

Gino Martina

Design and Implementation Expert

Our growing community

Our growing community

Nelly Rosa

Social Impact Reporter

Danique Joubert

Social media and marketing strategist

Taliet Marsman Ruiz

Creative researcher / maker

Guenna Gustina

Sample creator (2023)

Yaêl van Leijenhorst

Intern 'International Food and Agribusiness’ (2023)

You?

Send us an e-mail to join our community

Nienke Hoogvliet

Designer in Residence

(January - February 2024)

Sanne Muiser

Designer in Residence

(November 2023)

Loret Karman

Designer in Residence

(September 2023)